One of the things that first started me on the path to founding Pampa was photography. From a young age, I was always interested in learning about Latin America’s native peoples, especially those in my home country of Argentina. Documentary photography—photography that captures the philosophy, culture and folklore of indigenous communities—has always been a passion of mine.

When I started the Pampa journey by exploring remote parts of my country with my camera in hand, I stumbled across the work of many photographers with the focus on Andean communities, but Lucio’s work was by far inspired me the most. Noble, authentic, and raw—that’s how I would describe his work. There is no mask behind his lens. He represents real life and real people, with an added magic spice that makes your mind wonder.

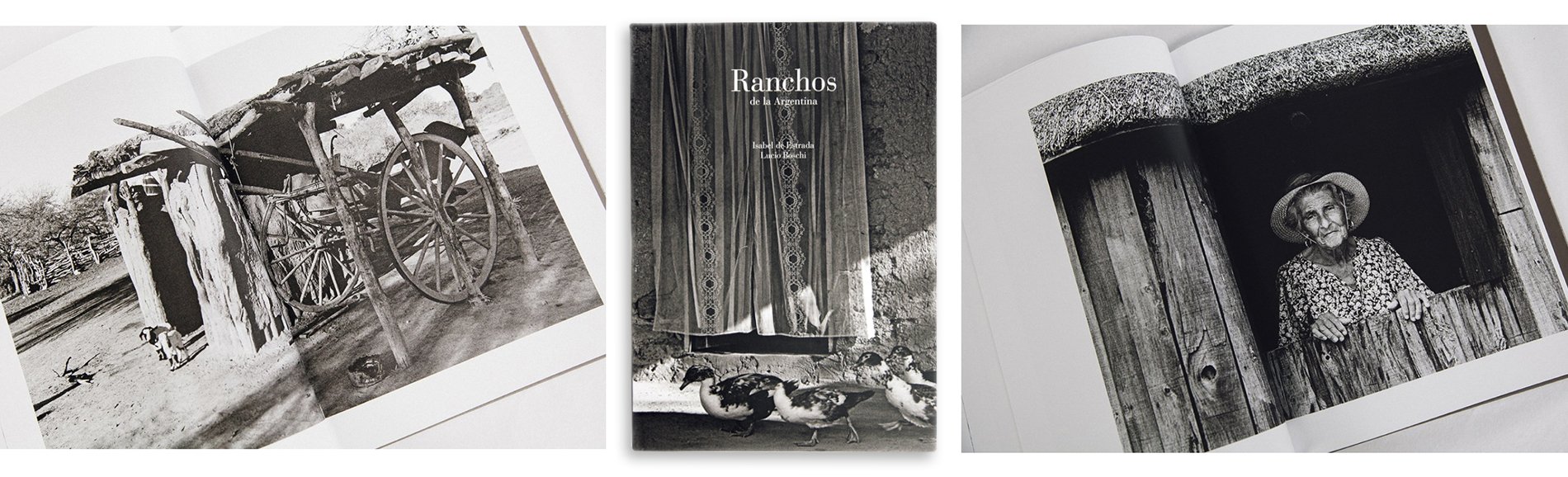

Not only has Lucio published many books (one of which you can purchase through our store here) and had solo shows around the world, he recently opened his own museum in Jujuy, Argentina, high up in the Andean mountains.

There are no signs in the main street to indicate the way to Museo En los Cerros (MEC), or Museum Between the Mountains. It’s a place that finds you. Lucio established the MEC as a way to give back to the local community through world-class photography exhibits and learning facilities. The museum is home to masterpieces by some of the greatest Argentinean photographers, all of whom donated their work to help Lucio realise his dream.

On my last trip to Argentina, I visited the MEC for the fourth time. Lucio’s work is so integral to Pampa’s story, I felt I needed to share this special place with you. I sat down with Lucio to talk about his own creative path and how he has helped others find their way.

Below is my interview with Lucio Boschi.

Victoria Aguirre

January 2018, Jujuy, Argentina.

Tell us a bit about your background. How did your passion for photography first start, and how has it evolved ?

I went travelling when I was very young—first to Northern Argentina, and then to different areas of the world. At that time, I was a very silent young man. I would come back from my trips and my friends or my mother would ask me about the places I visited or my experiences and I always answered the same thing: It was very nice, very interesting. It was difficult for me to talk about my feelings, about what I felt or what I saw. At the same time, I felt uncomfortable not being able to share experiences.

One summer I was travelling in Northern India and the Himalayas and I was invited to watch a slide show in a hotel in the mountains. I thought that it was a perfect way to tell stories, to communicate.

I bought a 12 pack of Kodachrome. From that moment on, every time I came back home, I would invite my friends and family to a slide show. I felt great. I knew very little of photography and taught myself—with many mistakes—how to work with the camera and the light.

How would you describe your photographic style?

I am a basic photographer and know very little of technique or modern tools. My images are direct black and white, sometimes dramatic, intense and thick as if you can chew the image.

What do you enjoy photographing the most?

I enjoy spending time with and photographing the daily lives and celebrations of the Andean communities. Theirs are sometimes the humblest and rawest forms of living.

How was your time living in Jujuy, and what was the biggest lesson you learned?

At some point I decided to settle in Northern Argentina, in a native community in the Andes. I bought a piece of land and built a basic house with adobes and stones. I lived for years without energy, phone or gas. I was trying to connect with the bare essentials: with the air, silence, and the stars. I became conscious of how happy I was by the fire, alone with existence.

What do you think about the situation now with indigenous people in Argentina?

It’s a complicated situation and it’s different in each ethnic group. I feel there is a lot of value in their knowledge, in their cosmovision, in the respect they have towards nature and Mother Earth. The responsibility to protect this is partly on the politicians, but also of each native group. In both cases, unfortunately, uneducated leaders held control and were the most representative for many years.

Where did the idea for MEC come from, and how did you make this dream of yours come true?

I was invited to show my work in many different museums and galleries around the world. Every time I talked about this with my Andean friends, they showed some doubt about it. Their images were on the covers of books. Their ceremonies were shown in distant places. At some point I thought it would be a good idea to do things the other way around and bring some art of the world to the mountains, to the community. Many other photographers felt the same way and donated their work to the museum.

What does MEC offer the community?

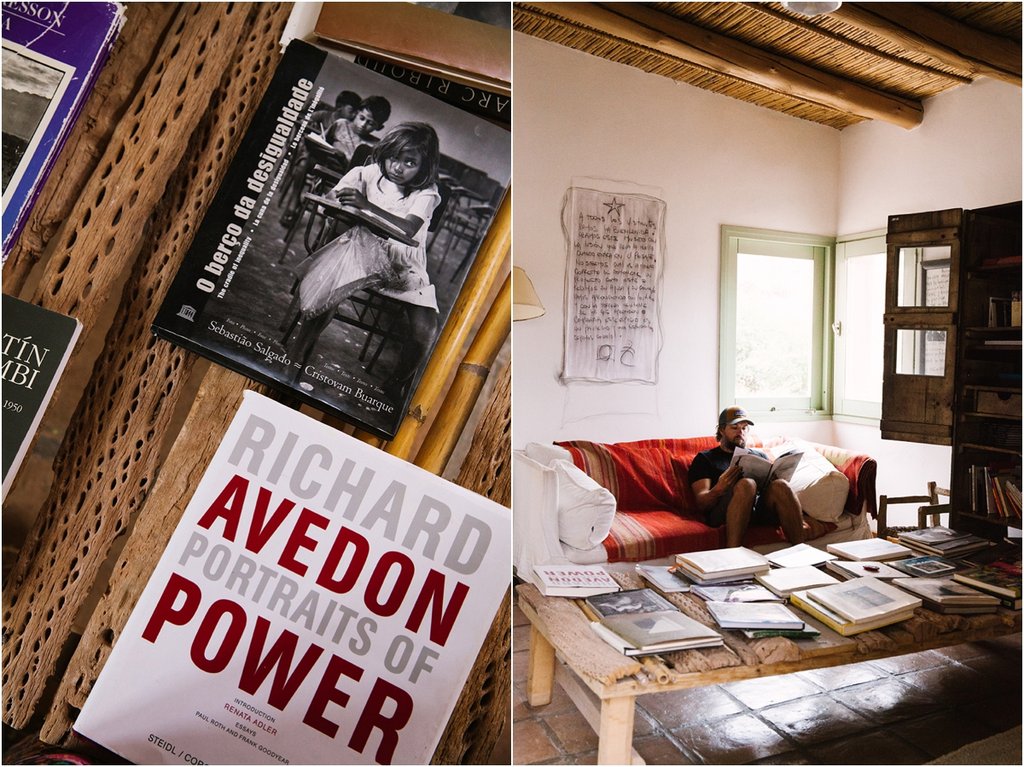

MEC has one of the best collections of Argentinean photography—yet it stands in the middle of nowhere. It is open to whoever arrives and it is a platform for students in the north. They come and stay for hours in the library; they bring their photographs and listen to lectures. We analyse their photographs and try to guide them and encourage them to continue. We get a lot of echoes back day after day, and we try to learn from that exchange.

Tell us about the beautiful MEC building and what you intend people to experience when they visit.

The museum was built in the traditional way, with stones and adobe from the area. The structure is similar to some family homes at La Puna, with small, connected spaces and patios everywhere. The idea is to respect the nature of the place from the outside and try to offer a modern concept on the inside, with white walls and good illumination.

It feels like the museum is hidden as there is no sign on the main road. Did you do this on purpose?

Yes. I feel that the museum is a little bit of a dream and we want to keep it that way, with a certain calm rhythm, with the mystery and blessings of the mountain. It is open to everybody, but it’s not that easy to get here. It’s like a secret revealed. I enjoy that.

If you had to choose, which of your books is your favourite and why?

Pueblos de Los Andes is my favourite because I produced it during those beautiful years I spent alone in the mountains with nothing but the essentials.

What other photographers do you admire?

I admire a lot of photographers. Josef Koudelka, Avedon, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Werner Bischof, Graciela Iturbide, Pentti Smmallahti, and above all Martin Chambi.

What are working on at the moment?

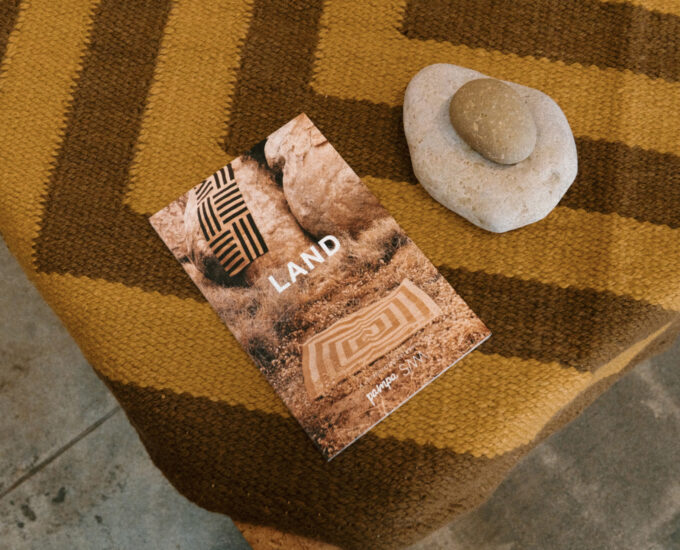

I am working on a new book and some exhibitions. I want to visit some distant villages I have never visited before in Jujuy and Salta. I am also doing a long-term project with Japanese photographer Yuriko Takagi. She takes photographs of a poncho weaver in the Andes and I take photographs of a Kimono designer in the Matsumoto mountains.

More of Lucio’s work: http://www.lucioboschi.com.ar

Visit the MEC: http://www.museoenloscerros.com.ar

Buy our Lucio’s Boschi book here

*All images are copyright of Pampa, for any kind of use please contact us at hello@pampa.com.au for permission.

Leave a Comment